Byzantine Art and Diplomacy in an Age of Decline Hillsdale Cambridge

As Latin Crusaders gazed intently at the urban center of Constantinople for the first fourth dimension in June 1203, Geoffroi de Villehardouin claimed that in that location was "no man so brave and daring that his flesh did not shudder at the sight."i Even docked at a distance from the illustrious Byzantine capital on the Bosphoros, rich palaces and tall churches could be seen beyond the metropolis's famed lofty walls and towers. While Constantinople had held a privileged position in the medieval Mediterranean every bit the heart of luxury, learning, and holy Christian relics since its foundation by Constantine the Great in the fourth century, the arrival and subsequent conquests of the Crusaders inaugurated a new era for the capital and the larger empire. After more half a century of Latin occupation (1204–61), which included the massive exportation of the urban center's most precious treasures, the Byzantines reclaimed Constantinople. Only the reconquest came at a great cost, and scholars have generally characterized the subsequent two centuries equally a period of decline marked by political fragility and economic scarcity.

In contrast to the awe of the European Crusaders, expressed in such visceral terms by Villehardouin, over a century afterwards in the mid-fourteenth century, Byzantine historian Nikephoros Gregoras lamented the diminished circumstances of his once-celebrated upper-case letter. After the coronation of Byzantine Emperor John 6 Kantakouzenos in 1347, Gregoras observed that in that location was nothing left in the imperial treasury "but air and grit and, as they say, the atoms of Epicurus."2 Nostalgic laments such every bit this accept shaped not only contemporary perceptions merely besides near modern scholarly assessments of what has come to be known every bit the Late Byzantine or Palaiologan period, or the period between the Byzantine restoration of Constantinople in 1261 and the final conquest of the urban center by the Ottomans in 1453. Nostalgia is a seductive sentiment. How can nosotros not exist moved by the fact that the Belatedly Byzantine imperial crown worn past John Six at his coronation was inlaid with mere colored glass, the original gems having been pawned to the Republic of Venice earlier in the century?iii

Notions of pass up and twilight, however, overshadow a reality of more than nuanced cultural relations during the Palaiologan period. In the face up of this economic and political adversity, classical instruction and intellectual life flourished. Indeed, fifty-fifty in lamenting the sad country of the treasury, Gregoras betrays his learned status and his ties to a long Hellenic heritage past describing bankruptcy (emptiness) in Epicurean terms. The visual arts thrived besides, as testified, for case, past the celebrated mosaics and frescoes of Constantinople's Church building of the Chora and the myriad icons and precious portable objects brought together in the Metropolitan Museum of Art'southward 2004 exhibition "Byzantium: Faith and Power, 1261–1557."4 The unsurpassed vibrancy of Byzantine art during this period has often been described, although somewhat problematically, as a "Palaiologan Renaissance," and a spate of recent exhibitions take paid tribute to the artistic traditions of later Byzantium on a grand scale.5 In jubilant the visual culture of the final two centuries of Byzantium, an acknowledgment of the empire's diminished political and economical continuing serves only to highlight the very strengths of its artistic traditions. Despite poverty and political fragility, the arts of the era held together the larger Orthodox oikoumene.6

This volume proceeds from the claim that the arts thrived in the face up of political and economic decline, but information technology further interrogates the particular mechanisms past which the visual arts defined after Byzantium. How and why were sure visual strategies adopted in the face of the pass up felt so acutely by Gregoras and other intellectuals of the fourth dimension? Furthermore, what sort of image did rulers of this impoverished empire cultivate and project to the wider medieval globe? Which particular ideological associations to the past were visually cultivated and which were elided?

Although scholars recognize the paradoxical discrepancy between economic weakness and cultural strength during this period, none of them has pursued an caption for this phenomenon. One way to understand this apparent enigma, this book suggests, is to recognize that later Byzantine diplomatic strategies, despite or considering of diminishing political advantage, relied on an increasingly desirable cultural and artistic heritage. In the subsequently Byzantine period, power must, out of economic necessity, be constructed in non-budgetary terms within the realm of civilization. In an attempt to reassess the role of cultural production in an era nearly oftentimes described in terms of decline, this written report focuses on the intersection of 2 central and related thematics – the imperial epitome and the gift – every bit they are reconceived in the terminal centuries of the Byzantine Empire. Through the analysis of art objects created specifically for diplomatic exchange alongside key examples of Palaiologan imperial imagery and ritual, this volume traces the circulation of the image of the emperor – in such sumptuous materials as silk, bronze, aureate, and vellum – at the end of the empire.

Drawing on diverse visual and textual materials that have traditionally been eclipsed in favor of the earlier Byzantine catamenia, this book interrogates the manner in which previous visual paradigms of sovereignty and generosity were adapted to suit diminished contemporary realities. It is therefore situated at the convergence of fine art, empire, and decline. In this style, this book expands discussions of cultural exchange and boundary crossings by prompting u.s. to question how the concept of decline reconfigures categories of wealth and value, categories that lie at the core of cultural exchange.

Pharmakon and apotropaion

In an encomium for Michael VIII Palaiologos, court orator Manuel Holobolos expresses the ability of the emperor's epitome as a gift. According to Holobolos, at the negotiations of the Treaty of Nymphaion through which the Genoese joined forces with Michael Palaiologos with the aim of recovering Constantinople (1261), the Genoese requested an image of the emperor equally a visible expression of protection and love for their city. The imperial image for the Genoese, Holobolos claims, would be a great remedy, a potent defence, an averter, a powerful parapet, a stiff belfry, and an adamantine wall.7 The word choices hither are pregnant. Not simply is the imperial epitome associated with key fortifications to protect a urban center (parapet, tower, wall), it is likewise described as a pharmakon (φάρμακον) and an apotropaion (ἀποτρόπαιον). The former, an ambiguous term, which can be translated in entirely opposite, almost contradictory ways, holds a privileged position in theoretical discussions of gift-giving,viii while the latter is suggestive of cult images and amulets. Holobolos thus ascribes to the imperial image an efficacy normally reserved for sacred icons in Byzantium.9 The Virgin's icon was understood to be particularly efficacious. The Akathistos Hymn hails the Theotokos as the "impregnable wall of the kingdom…through whom trophies are raised up…[and] through whom enemies fall," and her icon famously led battles and processions forth Constantinople'due south walls at central perilous moments.10 In the oration, withal, Holobolos is describing the authority of the image of the emperor, non the Virgin, and this raises complicated issues of majestic allegiance and hierarchy.

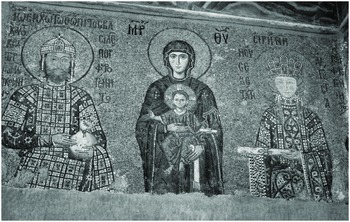

The royal image in Byzantium constituted the key visual manifestation of sovereignty, and it frequently commemorated imperial munificence. In the centre of the empire at Hagia Sophia, the celebrated suite of imperial mosaics on the easternmost wall of the south gallery conveys the broader ideology of imperial largesse through the representation of very specific acts of donation to the church (Figure 0.one). These panels present a double joint of imperial gift-giving separated past roughly a century: Constantine 9 Monomachos (r. 1042–55) and Zoe with Christ occupy the north side of the wall to the viewer'due south left (Figure 0.ii), and John Ii Komnenos (r. 1118–43) and Eirene with the Virgin and Kid announced on the south side to the right (Figure 0.3).11 The Macedonian and Komnenian emperors hold sacks of money, their monetary offering for the church, and the empresses carry scrolls with inscriptions, signaling a recording of the donation.12 The emperor'due south function equally benefactor of the church building is here made visually explicit, as purple largesse funded the celebration of the liturgy in the Peachy Church. The mosaics themselves in turn constitute a gift to the church, 1 that memorializes such imperial munificence.13

Effigy 0.1 Hagia Sophia, Constantinople, general view of the mosaics on the due east wall of the s gallery

Figure 0.2 Constantine 9 Monomachos and Zoe with Christ, south gallery mosaics, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople, eleventh century

Effigy 0.3 John II Komnenos and Eirene with the Virgin and Child, south gallery mosaics, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople, 12th century

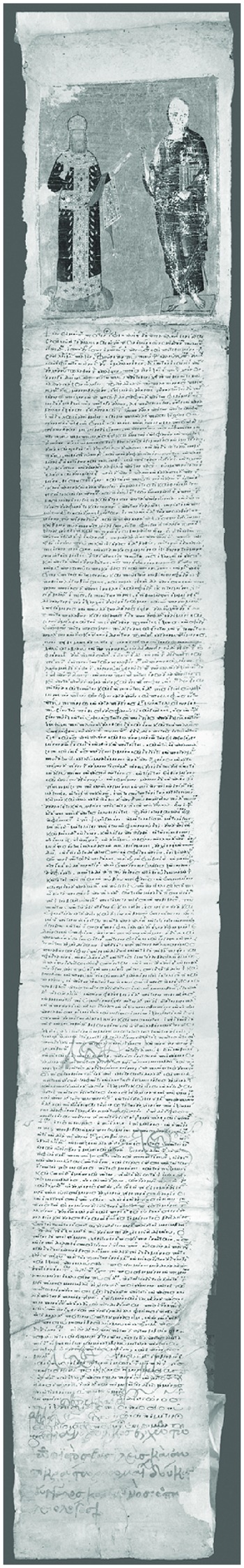

The middle Byzantine mosaics of the upper gallery of Hagia Sophia encapsulate the manner in which the royal function is inscribed through the ritual performance and visual commemoration of gift-giving. A key innovation in regal imagery in the later Byzantine period testifies to the continued if not closer alignment of the imperial image with largesse. The emperor's figure was included on acts of donation themselves, chrysobulls, for the first time in the early Palaiologan period.fourteen A number of chrysobulls adorned with illuminated portraits survive from the Palaiologan period, 3 of which are associated with Andronikos 2 (r. 1282–1328), including one currently in the Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens granting and extending the privileges of the metropolitan of Monembasia in 1301 (Figure 0.four).15 Composed of 4 vellum sheets, which joined together reach nearly 80 inches in length, the chrysobull concludes with the emperor'southward signature in deep reddish ink and commences with a miniature of Andronikos offering to Christ a rolled white curlicue meant to reference the chrysobull itself. The miniature thus depicts the emperor in the act of donating the very scroll that bears both the representation as well as the textual attestation of the souvenir itself. The purple portrait on Palaiologan chrysobulls such as this solidifies the emperor's gift in an near legal way, while simultaneously transforming the viewer into a witness to the transaction.16

Figure 0.4a Chrysobull of Andronikos II Palaiologos, 1301, Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens (BXM 00534)

Innovations such every bit this highlight the alignment of the imperial image and the gift in later Byzantium. Not surprisingly, in that location is a rich corpus of visual cloth that relates to imperial souvenir exchange in its various permutations. Accordingly, this book treats the afterwards Byzantine majestic epitome equally a souvenir, and a serial of objects that invoke gift-giving constitutes its archive. Not all the objects, however, are gifts per se. Chapter iii, for example, focuses on coinage, traditionally understood as the ways of economical exchange in contradistinction to the gift. Simply in Byzantium, the emperor dispersed coins bearing his figure in a ritualized performance much closer to giving than buying or selling. Moreover, in my reading of the radical innovations in numismatic iconography post-obit the Byzantine restoration of Constantinople in 1261, coins constitute an image of thanksgiving in and of themselves linked to the lost bronze awe-inspiring representation of imperial giving, which is the subject of Chapter 2. The other chapters examine objects created as gifts and extended to such varied sites as Genoa, Paris, and Moscow: ane explicitly associated with a diplomatic treaty, another offered at the conclusion of a failed diplomatic mission, and yet another post-obit upon a marriage alliance. Despite variations, all the objects nether investigation engage the activeness of giving, which is inflected with subtle though discernible calibrations of hierarchy. Furthermore, they all represent the emperor in relation to the action of giving. In this mode, this book associates the image of the emperor with the thing of souvenir-giving. As elucidated by a substantial body of anthropological scholarship, gift-giving is neither gratuitous nor disinterested, but rather works in complex ways to found and recalibrate contingent relations of power and hierarchy. For this reason, my attending to the imperial prototype as a gift provides a crucial optic for re-evaluating the reconfiguration of Byzantine sovereignty at a time of diminished political sway through i of its near important representations: the epitome of the emperor. Throughout the Byzantine Empire, the likeness of the emperor and majestic largesse consistently served as a centerpiece for diplomatic strategies. Rich source material from the middle Byzantine menstruation exposes the protocols of Byzantine diplomacy. These primary sources have been culled by scholars to demonstrate the centrality of imperial largesse to the notion of Byzantine identity. Royal sources adumbrate what kinds of gifts are appropriate for strange ambassadors, both at court in Constantinople and abroad, and they emphasize the diplomatic rituals of reciprocity and brandish every bit key to negotiations. The emperor, every bit the embodiment of empire, establishes and reinforces his superiority through extravagant demonstrations of largesse, and he solidifies alliances through such ways. It is through the giving of gifts and the resulting enactment of allegiances that the very contours of the empire are fatigued. Just this model becomes problematic when seen through the lens of the later Byzantine period and its constricted visions of imperium. If hierarchy is implicit in imperial gifts from Constantinople, what happens when the distance between real and represented grandeur becomes and so vast? In other words, if to give a gift – and an imperial image equally a gift in detail – is to inscribe bureaucracy and to position the recipient equally indebted, how can a gift from a beleaguered empire in the throes of disintegration convey superiority? What are the precise mechanisms by which giving tin all the same convey the greatness of its giver? These questions prompt a critical rethinking of our understanding of the period, non just of the role of Byzantium inside other cultural formations only also of the relation of the visual arts to empire, ascendency, and refuse.

Figure 0.4b

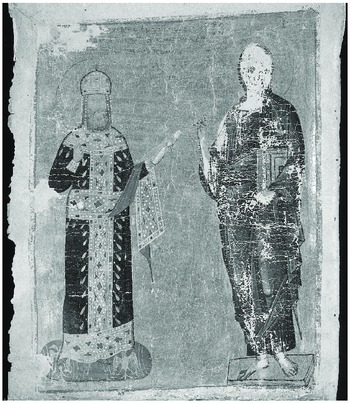

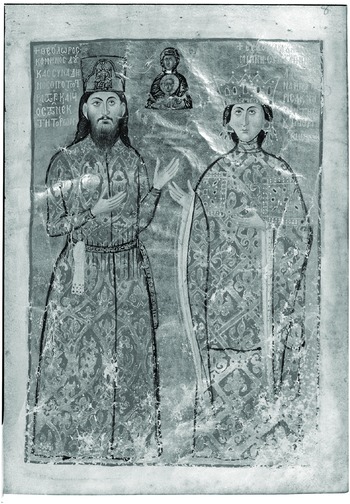

Another development of the Palaiologan period underscores the power of the emperor's portrait to proclaim his suzerainty: the purple image became codified as official insignia in court dress in the afterwards Byzantine menses.17 Pseudo-Kodinos explicitly describes a headdress that bears an imperial portrait as a skaranikon,18 representations of which are attested in near media, both portable and monumental.19 Amidst the most notable examples is the fourteenth-century typikon for the convent of the Female parent of God of Certain Promise in Constantinople, known as the Lincoln Higher Typikon, which includes a serial of portraits of family members such as Theodore Synadenos wearing precisely this tall headdress adorned with the effigy of the emperor (Figure 0.5).20It is besides depicted on a grouping of anonymous courtiers in the fresco cycle of the Akathistos Hymn on the eastern wall of the narthex of the Katholikon of the Holy Trinity in Cozia, Valachia (Figure 0.6).21 Here a group of dignitaries wearing skaranika, which bear a bust-length outline of the emperor, stand behind the emperor himself, who gestures in reverence toward the icon of the Virgin at the heart of the composition, which is mounted above an embroidered podea echoing an epitome of the emperor in prayer. Such an paradigm, which takes as its inspiration the twenty-third strophe of the Akathistos, brings together two of Byzantium'south nigh potent images – that of the Virgin and of the emperor – and showcases each of them as worthy of veneration and emulation.

Figure 0.five Portrait of Theodore Komnenos Doukas Synadenos and Wife, Lincoln College Typikon, Bodleian Library, MS. Lincoln College gr. 35, fol. 8r, c. 1327–42

Figure 0.half-dozen Detail of the fresco cycle of the Akathistos Hymn from the Katholikon of the Holy Trinity in Cozia, Valachia

The skaranikon served to visualize majestic and courtly authority in clearly legible sartorial terms: it glorified the imperial role by picturing the figure of the emperor equally the source, even the defining feature, of the elevated status of its wearer.22 The royal paradigm was conceptualized as a privilege to exist worn equally a symbol of allegiance, precedence, and rank. Only a privileged few were given the honor of wearing the emperor'south likeness. Although the emperor's image as a codified sartorial component of the imperial court hierarchy originates in the Palaiologan menstruum, the imperial paradigm was deployed diplomatically much before. The emperor'due south likeness proclaimed his suzerainty both within the empire and within the realm of foreign diplomacy.23 To offering an majestic prototype every bit a gift is to inscribe Byzantine hierarchy. It is to prescribe allegiance through an act of seeming generosity, and the logic of this contradiction relates to the hierarchical stakes of gift-giving more than broadly.

Historicizing imperial giving

A contradiction lies at the heart of the term "souvenir." The Oxford English language Dictionary emphatically stresses the gratuitous and disinterested nature of a gift, only it is hither understood as deeply imbued with agendas of hierarchy and reciprocity.24 A souvenir, in general usage and by definition, is something freely given; information technology is predicated on a lack of self-involvement. Whether property, a affair, an experience, or fifty-fifty personhood itself, a gift is offered in commutation for nothing. Yet anthropologist Marcel Mauss in his Essai sur le don famously declared that there could be no gratuitous gift and that giving always involves self-interest to a sure degree.25 From a philological-linguistic perspective, Émile Benveniste has traced the clashing etymology of the souvenir in Indo-European linguistic communication, demonstrating that the languages of giving and taking are intimately related.26 Later on Jacques Derrida called the complimentary gift further into question, challenge that there could be no gift at all, let lone a free i: to requite ever already negates the giving.27

At its core, Mauss'south report of the gift represents a commitment to the principle of reciprocity. Cyclical rather than last, gifts, for Mauss, instill 3 obligations: to give, to receive, and to return. Anthropologists and social scientists accept taken outcome with the spiritual logic of this reciprocal model and in detail with the mechanism compelling reciprocation or the spirit of the matter given. For others, Mauss's work serves as a springboard for related aspects of prestation28 such as debt, expenditure, and largesse. Maurice Godelier, for case, revisits Mauss in order to consider sacred objects that do not circulate, proposing that the logic of such gifts concerns the ungiveable, a proposal similar in many ways to Annette Weiner'southward examination of inalienable possessions, which were meant to be guarded rather than extended as gifts.29 Complicating Mauss'due south cracking cyclicality, Pierre Bourdieu characterizes the gift as a profound articulation of hazard by highlighting the associated elements of contingency and implied danger that result from the fundamental dubiousness of whether, what, or when a return or counter-souvenir will appear.thirty He thus reads giving as merely an incomplete gesture, emphasizing that the cyclical nature of the substitution – the paths, logic, and effects of gifts – can only be appreciated fully in retrospect.

Much of our agreement of medieval conceptions of gift exchange is due to the survival of the Book of Gifts and Rarities (Kitab al-Hadaya wa al-Tuhaf), an Arabic compilation of ceremonial courtroom exchanges.31 The linguistic communication of reciprocity is explicit in Standard arabic, which exhibits a finely tuned semantic range for expressing gifting. Ii different words for "gift" are specified: one signifies a contract with no expectation of render and is used commonly for diplomatic gifts, while a second implies the obligation of a return gift from the recipient. The distinction, in other words, is between conditional and unconditional gifts.32 An often-cited chestnut from this medieval compilation explicates the competitive nature of gift-gifting cross-culturally. The text reports the response to a gift sent past a Byzantine emperor to Caliph al-Ma'mun with the following instructions: "Send him a gift a hundred times greater than his, so that he realizes the glory of Islam and the grace that Allah bestowed on us through it."33 This passage confirms the bones premise advanced past anthropologists that giving is fundamentally agonistic and that it triggers shifts in power and divergence. Hierarchy, this passage suggests, is articulated through the transfer of sumptuous presents.

Anthony Cutler has elucidated the dynamics of prestation in the context of this text alongside contemporary Byzantine sources in relation to anthropological theories. Evaluation or cess, for example, is one point of similarity between the Arabic Book of Gifts and Rarities and the roughly contemporaneous Greek compilation of court ceremonial known as the Book of Ceremonies.34 In the business relationship of the regal reception of Olga of Kiev in Constantinople, the Byzantine source emphasizes souvenir cess: the text relates how the gift is brought first "to the magistros so that he knows what each souvenir [is worth], and then that he will be able to recall to the emperor at the fourth dimension of the exchange of gifts what he should return through his ambassadors."35 Diplomatic gifting at the highest level of the imperial administration, this episode suggests, involved careful calculation. Although this Greek text lacks the explicitly agonistic aspect of prestation found in the Kitab al-Hadaya, information technology makes it abundantly clear that souvenir exchange was strategic and that giving ultimately concerned getting.

The strategic necessity of thinking about gifts in the diplomatic context is elucidated by a 10th-century Byzantine packing list that specifies luxury items to exist brought on military expeditions for distribution to foreigners.36 According to the specifications of this prescriptive listing, the imperial vestiarion'due south load should include the purple regalia, clothing, and items of imperial ceremonial (vessels, swords, perfumes, textiles, etc.), books (liturgical, strategic and prognostic manuals, and histories), and miscellaneous medical substances.37 In addition to these items, according to the text, both textiles and specie were to exist included for distribution. Tailored and untailored cloths of varying degrees of quality and with an abundance of decorative features from stripes to eagles, royal symbol, and hornets, all with precisely specified monetary values, were to be brought along to be dispatched to distinguished powerful foreigners.38 Simply the question of how such largesse should be distributed apparently required judiciousness. An anonymous sixth-century Byzantine treatise on strategy speaks of the importance of training envoys in the arena of diplomatic gift commutation. An ambassador sent on a mission begetting gifts must approximate whether to extend all the gifts brought along, to retain the most valuable, or to hold back the gifts and official messages birthday and evangelize just expressions of friendship.39 The text suggests that the middle ground – offering some of the gifts but not all of them – is the best selection when dealing with a potential aggressor equally it reduces hostility without enriching the enemy.twoscore

A disquisitional methodological point emerges from these sources. Generally gifts were extended strategically equally office of negotiations for or celebrations of peace, a peace that often did not terminal the lifetime of the gift itself. To read gifts as bear witness for friendly relations is therefore to miss the active role they played in establishing those very relations by their substitution; information technology is to miss their bureau in the political sphere. A recognition of the strategically significant motivation of giving prompts us to encounter an element of want in gifts. If giving is strategic, as contemporary sources make clear, gifts possess a measure of the optative, the linguistic annals or grammatical mood of wish or desire. Objects extended every bit gifts, it is here suggested, cannot exist read every bit evidence for social relations in a straightforward way. A souvenir rarely illustrates political fidelity, just rather is oftentimes exchanged in an attempt to constitute such allegiance. A liturgical vestment sent from Constantinople to Moscow in the early on fifteenth century, for case, visually celebrates the intertwined sacro-imperial dominance of the Byzantine capital letter (Figures 5.2–5.5). Simply my reading of the complicated program of this sumptuous vestment in Chapter five situates the motivation of its commission precisely in the loosening of purple ties with Moscow. Likewise, as argued in Chapter 4, the palatial manuscript sent to Paris at roughly the same time is motivated by failure rather than success (Figures 4.3–4.iv). Its commissioning follows on the heels of the emperor'due south protracted, and ultimately failed, mission to Western Europe in an attempt to secure aid for Constantinople. These gifts, in other words, were extended in the hope of strengthening ties and building support. Their entire organization was fundamentally strategic and contrived to underscore the Byzantine desire for future fidelity.

There are further methodological implications for invoking analytic tools derived from the field of anthropology inside the subject area of art history. In theorizing material gifts, anthropologists and social scientists accept for the most office focused on tangible appurtenances of a somewhat generic grapheme, such as foodstuffs or kula shells. The formal particularities of individual objects generally lie outside their analysis and thus the contexts of exchange are privileged over the objects of exchange. On this betoken, art historians are positioned to offer a significant intervention. The tools of assay item to the subject – stylistic, technical, iconographical, and other – allow for a thorough investigation of the specific material and formal properties of medieval gifts and prestation. It is one thing for textual scholars to recognize the power and hierarchy inherent in souvenir commutation, and quite another for art historians to elaborate precisely how such agendas are visually constructed by relying on texts, objects, images, and spatial environments.

Nonetheless, anthropologists take taught us to recognize the importance of the ritual context in which gifts are exchanged as well as the social relations triggered by their exchange. An business relationship of the visual dimensions of prestation therefore entails an examination of how the dynamics of obligation and reciprocity are visually encoded non only in objects and images merely likewise in the spaces of their formalism performance, display, or concealment. Robin Cormack, for example, has considered the royal palace of Constantinople as the ritual setting for the enactment of authority through gift-giving.41 In addition to environments of souvenir exchange, gifts themselves accept been the subject of recent study, as scholars take begun to consider classes of gifts and patterns of exchange, as well as individual fine art objects created equally gifts, with attention being paid both to their initial offering and to their reception and transformation over fourth dimension.42 Moreover, recent scholarship has attended to the mobilization of gifts in the political, dynastic, and sacred spheres throughout the medieval earth. As such scholarship makes clear, medieval gifts intervene diplomatic cross-cultural encounter, they mediate familial and dynastic relations, and they triangulate sacred transactions as votive offerings.43 In these various contexts, gifts negotiate rivalries and as well serve as agents of marriage.

The conceptual framework of the gift equally starting time elaborated in the field of anthropology thus opens up broad avenues of art historical study. While a single unified theory cannot adequately capture the complication of private objects and visualizations, understanding gift substitution every bit a powerful mediating agent in social and sacred dynamics is central to its productivity. As inherently relational, the souvenir operates on an optative register as an active agent of social bond and fracture, and information technology obliges and orchestrates ability relations among individuals and sacred economies. A recognition of the entangled agendas implicit in the diverse visual cultures of prestation allows us to come across the objects of assay not as mere passive reflections of social and sacred relations but as integral to the production of those relations.

The gift and hindsight

With its focus on the apportionment of the purple image and the gift in the increasingly cosmopolitan later Byzantine diplomatic arena, this book sits at the convergence of a number of key areas of research. Historians have provided comprehensive analyses of foreign diplomatic protocol, practice, and objects.44 The later Byzantine period, however, often figures equally a mere offshoot, or even an unfortunate coda, to the more prominent before menses.45This surely relates to the discrepancy between the political reality of the later period and its self-representation, which is described by Nicolas Oikonomides as a "constant opposition betwixt a glorified past on the i hand and the cold facts of the fourth dimension on the other."46 In lite of this opposition, it is difficult to avoid evaluative judgments, according to which diplomatic strategies of the menses are inevitably deemed unsuccessful.47 The ways and ends of later Byzantine diplomacy are fundamentally in conflict. At least since Edward Gibbon, reject is inevitably associated with fall.48 With hindsight, mod scholars who know that the end of the empire was near cannot assist but negatively evaluate late Byzantine diplomatic strategies. But this book attempts to suspend such judgment. The perception of decline, testified by intellectuals such every bit Gregoras with his lament most the pauper "atoms of Epicurus" in the regal coffers of his day, does not necessarily signal defeat. For those historical actors living through the turbulent later Byzantine period, the perception of refuse did not inevitably and teleologically result in the empire'south fall.

The interruption of evaluative judgment stems from the need to meet continuity and change in non-teleological terms. Certain aspects of the glorified past, including imperial imagery, were maintained in the face of decline in the Palaiologan period. But despite the conservatism of imperial imagery in general,49 in the final centuries of Byzantium we run across subtle though discernible innovations. Indeed, equally discussed above, the addition of the emperor'south portrait to chrysobulls during this later Byzantine flow represents one such innovation, as does the introduction of the emperor's effigy to official courtroom dress, where the skaranikon designates royal fidelity in clear visual terms – and again, representations of court officials and dignitaries wearing skaranika survive in an impressive array of media from the Palaiologan menstruum. Equally the following chapters brand clear, even when largesse was compromised past an economic scarcity that rendered the generous royal ideal highly problematic, the regal prototype was extended every bit a gift in the most urgent diplomatic contexts. This book thus insists that refuse itself is not simply negative, simply also contains a recuperative, even generative, dimension. It asks, in other words, what decline enables. What new patterns of artistic practice, patronage, and munificence emerge in the face of refuse?

Organization

The trajectory of Byzantine Art and Diplomacy in an Historic period of Decline is governed by the physical heart of the empire, Constantinople. The first part of the book centers on Constantinople's reconquest from the Latins in the thirteenth century; the urban center's eight-year-long Ottoman siege following the devastating civil wars in the fourteenth century motivates the second half. The beginning of the Palaiologan menstruum and its near stop, in other words, provide the frame for the book.fifty Under the rubric "Adventus: the emperor and the city," the three chapters that comprise Part I appoint the 1261 Byzantine restoration of Constantinople. Collectively they investigate the visual negotiation of legitimacy and sovereignty in the opening years of the later Byzantine Empire through three key images of Michael 8, the showtime Palaiologan emperor, that appoint in differing manners the Byzantine restoration of the royal metropolis, which was conceptualized as a divine gift.

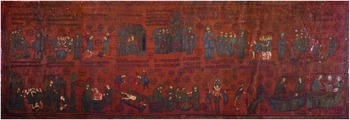

The opening chapter, set in the years immediately preceding the reconquest of Constantinople, provides a sustained analysis of a silk fabric, or peplos, sent to Genoa equally office of the 1261 Treaty of Nymphaion, the treaty through which Michael, then emperor in exile in Nicaea, formalized an alliance with the Commune of Genoa in an attempt to reconquer Latin-occupied Constantinople. At the center of the silk, the emperor is depicted being led into the church of Genoa framed past a detailed hagiographic bike of St Lawrence, the patron saint of the Genoese church for which the silk was destined (Effigy 1.1). Through the imbrication of imperial image, hagiographic narrative, and political pact, this diplomatic gift is read in Chapter ane as a visual encomium to the emperor and to imperial transaction on the eve of the defining event of the later Byzantine menstruum and the event for which the peplos was custom-created: the render of Byzantine rule to the royal city.

Effigy 1.i Embroidered silk of St Lawrence, associated saints, and Michael 8 Palaiologos, 1261, Genoa, Civiche Collezioni, Museo di Sant'Agostino

Subsequently 1261, the emperor historic the Byzantine restoration of Constantinople through a new visual vocabulary of thanksgiving, as evidenced by a monumental bronze statue erected in the restored metropolis and a related purple pattern serially struck and circulated on gold coins, the subjects of Capacity ii and 3, respectively. Read as the emanation of a fundamentally fraught reign, the statuary monument depicted the emperor offering a model of the imperial city to the archestrategos and was erected in front of the Church of the Holy Apostles as role of the emperor's agenda of association with Constantine the Cracking. Analysis of this no longer extant monument elucidates the trouble of legitimacy, one of the central contested issues facing the early Palaiologoi. Beyond forging visual and thematic connections with other majestic monuments from the past throughout the recently restored city, this chapter proposes that the lost monument commemorates imperial genealogy while simultaneously participating in the inauguration of a new iconography of the prostrate emperor, ane that signals a profound shift in royal ideology.

Royal gilded coinage, in all likelihood, provided the most immediate pictorial source for the lost bronze monument. Like the bronze monument, gold coins struck afterward the imperial restoration of Constantinople depicted the emperor on his knees in a visual dialogue that similarly engaged issues of thanksgiving and legitimacy. The contrary of Michael VIII'south gold hyperpyron represents the emperor on knee being presented by his angelic advocate to Christ, and the obverse presents an epitome of the orant Virgin surrounded by the walls of Constantinople (Figures 3.2–3.4). Chapter 3 reads this unprecedented iconography according to the transactional logic of displaced giving and imperial instrumentality, a concept emphasized in rhetorical sources of the period. Coinage, the very medium of economic substitution that crossed geographical and political boundaries, disseminated this specific vision of imperium to a wide context and is thus ideally suited to trace the apportionment of the new image of the emperor for the much-changed subsequently Byzantine Empire. This affiliate advances the claims of the previous chapter in its give-and-take of the innovative visual rhetoric inaugurated by the purple capital letter's reconquest, only information technology also constitutes the transition to Part II, in that information technology traces the numismatic reconfigurations prompted by the instability of Palaiologan succession, and the rupture of the fourteenth-century civil wars when Byzantine gold ceased to be struck altogether.

In examining the fine art and politics of the restored Byzantine uppercase, Part I argues for the instantiation of a new and distinctly Palaiologan purple prototype. Information technology further assesses the nature of the empire's restoration. What previous models of dominion were evoked and at what cost was the restoration effected? The large silk peplos sent to the Italian maritime city, also as the monumental statuary effigy of purple gift-giving and the serially struck gold coins, usher in a period where largesse would be compromised by an economic scarcity that rendered the generous majestic platonic more than problematic. Inside the new economic constraints of this age, what patterns of artistic practice, patronage, and largesse emerged?

Part Ii of the book provides some provisional answers to these questions. Under the rubric of the "'Atoms of Epicurus': the imperial prototype as souvenir in an historic period of decline," Chapters four and v plow to diplomatic gift-giving strategies in the early fifteenth century. These chapters argue for the cultivation of two distinct later Byzantine imperial identities: that of the emperor every bit custodian of a long and venerable philosophical tradition and also as the guardian of Orthodox spirituality. In the restored only politically and economically unstable diplomatic arena of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, new diplomatic souvenir-giving strategies needed to be adult. Byzantine textiles, icons, and relics were still extended as gifts every bit they had been in earlier times, though often recycled and re-gifted, just their status across the Mediterranean was significantly diminished every bit the silk merchandise had been demonopolized, trade routes relinquished, and sacred relics looted past Latin crusaders.

New sources of value for commutation with the courts of Western Europe were required, and Greek learning was cultivated in order to meet this diplomatic need. Chapter 4 takes every bit its focus an illuminated manuscript of the Neoplatonic writings of Pseudo Dionysios the Areopagite that was sent to Paris in 1408 after Manuel II'south extended diplomatic mission to the West (Figures 4.3–iv.4). By tracing the elaborate genealogy of past gifts to which it relates, this chapter sees this book as part of a conscious fostering of Greek studies on the role of the Byzantine purple administration. The Renaissance fascination with Hellenism emerges here equally an informed Byzantine diplomatic strategy: the purple court recognized western desires for Greek texts and, taking advantage of that interest, fostered Hellenic studies through gifts of manuscripts and teachers.

A vastly dissimilar visual rhetoric was employed within the larger Orthodox oikoumene. One outcome of the tenuous socio-political climate of the era was that Orthodoxy itself became the subject of diplomatic negotiation. In the first of the Palaiologan flow, Michael Viii attempted to subject the Byzantine Church building to Rome at the Council of Lyons (1274), and in the final years of the Palaiologoi, John 8 agreed to a unification of the Eastern and Western Churches at the Council of Ferrara-Florence (1438–9). The tension between Byzantine spirituality and empire – and in particular an impoverished empire – is explored in Chapter 5, which considers an elaborate liturgical vestment made in Constantinople and sent to the metropolitan of Kiev and all of Russia in the early fifteenth century (Figures 5.2–5.5). Embedded within the elaborate liturgical cycle are representations of the futurity Emperor John VIII alongside his bride Anna of Moscow, in addition to her parents and the Metropolitan Photios, who was appointed by the patriarch of Constantinople. While the vestment celebrates the matrimony through matrimony of the Muscovite and Byzantine regal houses, it ultimately emphasizes Orthodoxy every bit the source of their unity to a higher place all. Affiliate v argues that imperial Constantinople is positioned as the source for Orthodoxy, and in this way the sakkos is read as a visual analog to the celebrated letter of Patriarch Anthony reminding the G Duke of Moscow that there could exist no church building without the empire.

By taking equally a point of divergence art objects themselves – their agency, status, and social lives – the present study brings conceptual issues of cultural exchange to the physical level of fabric culture. The theoretical stakes therefore hinge upon the status of the fine art object. Post-obit anthropologists who study the "social lives of things," to borrow a phrase from Arjun Appadurai, this book assumes that gifts from the beleaguered belatedly Byzantine Empire contain the kind of agency unremarkably associated with individuals rather than objects.51 As extended gestures of their givers, they become metonymic evocations of the desires and aspirations of their creators. While I insist on the strategic nature of gifts – and accordingly read their visual programs in light of the very precise political and ideological contexts of their creation and dissemination – it is imperative to distinguish betwixt intention and reception, and to acknowledge that gifts mediate a eye basis. The analyses in the pages that follow are driven by the objects of analysis themselves and their precise formal and cloth properties. This book thus remains rooted in the techniques of art historical inquiry and hence attends to the particular formal idiom expressed in each instance. The item rationale for the focus on things, however, is to be found in the historiography of Byzantine art itself inside the wider fine art historical field. The insistence on looking closely at detail moments, monuments, and trajectories of cultural encounter serves as a means of countering broad generalizations about Byzantine pictorial "influence," where the eastern empire is rendered passive and unchanging in a teleology that privileges the rise of the West. By interrogating the concrete transfer of objects, this book seeks to provide a more nuanced and dynamic account of medieval artistic exchange, one that takes into account the temporal dimensions of ability and the changing fates of empires.

Source: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/byzantine-art-and-diplomacy-in-an-age-of-decline/introduction-the-imperial-image-as-gift/70C85A2F0BED11DC4D02B9702946687D